The 4 Steps to Process (Not Suppress) a Difficult Emotion Like Shame or Anger

10/13/20255 min read

The 4 Steps to Process (Not Suppress) a Difficult Emotion Like Shame or Anger

When a wave of intense emotion hits—whether it’s the hot rush of anger after an inconvenience/argument or the cold, sinking feeling of shame after a mistake—our first, most human instinct is to run, fight, or hide.

We scroll, we lash out, we overeat, or we distract ourselves until the feeling fades. This is called suppression, and while it offers temporary relief, it’s like stuffing a volatile gas under a fragile lid. Eventually, it leaks out as anxiety, stress, or chronic physical tension.

Emotionally intelligent people don't try to eliminate painful feelings; they learn how to process them. Processing means moving the emotion through your body and mind so it can deliver its message and exit cleanly, instead of getting stuck.

This isn't just fluffy self-help; it’s rooted in how the brain works. Your feelings are just signals. Anger is a signal that a boundary has been crossed. Shame is a signal that a social connection is threatened. Once you get the signal, you can move the feeling out.

Here are the four science-backed steps to process any difficult emotion, allowing you to move through pain without getting stuck in it.

Step 1: Name It and Normalize It (The Pause)

When strong emotion strikes, the brain's Limbic System (the alarm center) goes on high alert, bypassing the logical Prefrontal Cortex (PFC). Your first goal is to interrupt this hijack and bring your logic back online.

The Science: Affective Labeling

Neuroscience calls this technique Affective Labeling. Studies show that when you put a label on an emotion (e.g., "I feel anger"), the activity in the emotional centers of your brain (like the amygdala) immediately decreases. You move from feeling the emotion to observing the emotion.

The Practice: Stop, Drop, and Name

Stop the Action: Physically halt whatever you are doing (put down the phone, stop typing, pause the conversation). Do not react.

Drop Anchor: Take three deep, slow breaths. Focus on the physical sensation of your feet on the ground or your back against a chair. This pulls your nervous system out of "fight or flight."

Name It: Ask yourself, "What am I actually feeling right now?" Use specific language:

Instead of: "I'm having a bad day."

Try: "I am feeling frustrated and a rush of defensive anger."

Try: "I am feeling intense shame about that mistake."

By naming it, you create a tiny bit of space between You and the Emotion. You are not the anger; you are the person observing the anger.

Normalize and Validate

Once named, remind yourself that this feeling is universal and valid.

If it’s anger: "It makes sense that I feel anger when my boundary was ignored. This is a normal, protective response."

If it’s shame: "I feel shame because I am a human who made a mistake, and my brain is worried about being rejected. Every human feels this."

This step stops the emotional escalation and prevents you from layering judgment or guilt on top of the existing pain.

Step 2: Locate and Allow It (The Release)

We mistakenly believe emotions live in our heads, but they are physical sensations. Shame can be a heat in your chest; anxiety is often a knot in your stomach. To process the emotion, you must allow your body to be the container for the feeling.

The Science: Radical Acceptance

This step is rooted in Radical Acceptance (a concept from Dialectical Behavior Therapy, or DBT). Acceptance doesn't mean you like the feeling; it means you stop fighting the reality of the feeling's presence in your body. When you resist, you prolong the pain. When you allow, you signal safety to your nervous system.

The Practice: Body Scan and Curiosity

Locate the Sensation: Close your eyes, or soften your gaze, and scan your body. Where does the emotion physically live?

Anger often lives: In the jaw, shoulders, and a rush of heat or energy in the hands.

Shame often lives: As a contraction, a knot, or a heavy, cold feeling in the stomach or chest.

Become Curious: Use the language of neutral description, not judgment. You are a scientist studying a phenomenon.

"I notice a tightness in my throat."

"The heat in my face is about a 7 out of 10."

"The knot in my stomach feels heavy and slightly vibrating."

Allow It to Move: Don't try to fix or suppress the sensation. Simply tell yourself, "I will let this sensation be here for the next 60 seconds." Emotions are energy in motion. When you stop fighting them, they typically peak quickly and start to dissipate. They often last less than 90 seconds in their purest form.

Step 3: Discern the Message (The Logic)

Once the raw, physical intensity of the emotion has dropped (which usually happens after a few minutes of conscious allowance), you can engage your logical brain (the PFC) to understand why the signal was sent.

The Science: Cognitive Restructuring

This step uses principles from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which focuses on identifying the underlying thought that triggered the emotion. Your goal is to move from the intense feeling to the cold, hard fact or interpretation that caused it.

The Practice: The Why and The What

Unpack the Triggering Thought: Ask yourself:

What was the thought that triggered this feeling? (e.g., "If I make a mistake, I'm going to be fired and everyone will know I'm an imposter.")

What story am I telling myself about this event? (e.g., "The story is that I have to be perfect to be worthy.")

Identify the Core Need: Every difficult emotion points to a core unmet need. What is this feeling trying to protect?

If the emotion was Anger: The need is often Respect or Safety (A boundary was violated).

If the emotion was Shame: The need is often Belonging or Connection (The brain fears isolation or rejection).

Find the Fact: Challenge the story. Shame rarely feels better until you speak the facts of the event without the self-judgment. Self-compassion is of the utmost importance.

Story: "I am an idiot and I ruined everything."

Fact: "I missed the deadline on Project X, which caused a delay, but I immediately offered two solutions to mitigate the damage."

By separating the objective fact from the subjective, catastrophic story, you neutralize the emotion's power.

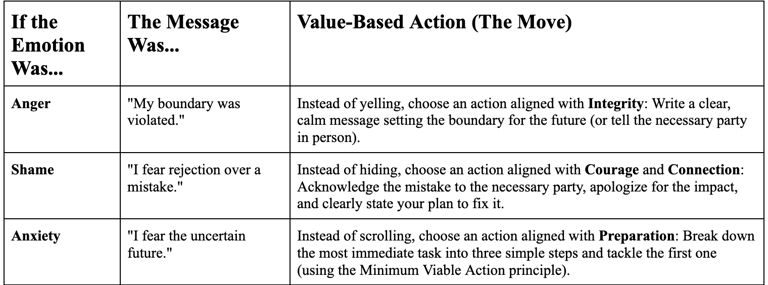

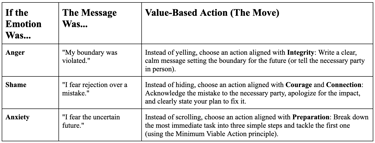

Step 4: Determine the Value-Based Action (The Move)

Emotions demand action, but most people act impulsively (yelling, hiding, etc.). After processing, you are ready to choose an action that is deliberate, effective, and aligned with your values.

The Science: Value-Based Living

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) encourages clients to choose actions based on their deepest values, even when they feel uncomfortable. The processed emotion informs the action, but doesn't dictate it.

The Practice: Choose Your Wise Move

Ask yourself: "Given my values (e.g., integrity, kindness, effectiveness), what is the most helpful next step I can take, even if it feels uncomfortable?"

The Path to Emotional Freedom

If you take anything away from this post, let it be this: Processing difficult emotions is not a one-time fix; it's a daily practice of showing up for yourself with courage, compassion, and curiosity. The next time a wave of shame or anger washes over you, remember: you don't have to fight the feeling. You just have to pause, allow it to deliver its message, and use that wisdom to take a single, self-respecting action.

Which of these four steps—Pausing, Locating the Sensation, Discernment, or Value-Based Action—feels like the biggest challenge for you right now? I'd love to hear your thoughts down below!

If you’d like to continue this beautiful self journey, here are some more posts you'll love!

Get in touch!

Feel free to share your thoughts, tips, and posts/products you like to see!